- Author Jason Gerald [email protected].

- Public 2023-12-16 10:50.

- Last modified 2025-01-23 12:04.

Great writers can blow you away when you read the first few sentences and keep you glued to keep reading until the end. You may wonder how they came up with sentences like this, or you may wonder how these writers started a story. The techniques in this article will help you craft compelling sentences and create strong concepts for the story. You'll learn how to start a short story, choose an opening for the story, and edit that opening.

Step

Method 1 of 4: Start Writing

Step 1. Try to write the gist of the story in one process without stopping or pausing

One way to write is to sit down and start with the heart of the story, then write down the details of the story without stopping to finish. Maybe this is a fun, fun story you'd like to tell a friend but you're confused about how to put it into a short story. Write down all the raw data or details of your story, then only then combine those details into a single whole.

- Focus on telling simple stories and write those simple stories. It may take you an hour or a few. Let's say you're talking to a good friend and tell him about the incident over coffee.

- Avoid research or extracting information beyond the story you want to tell. Try not to procrastinate thinking too deeply about the parts of the story. You'll find problems, but whatever they are, you can fix them later.

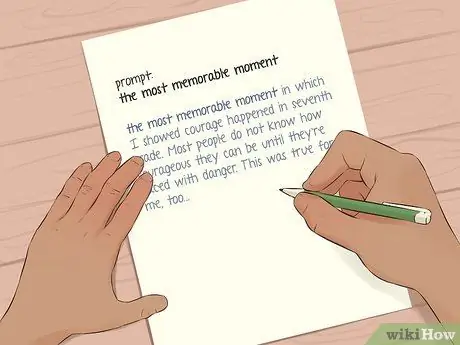

Step 2. Use the writing guide

If you're having trouble coming up with story ideas, you can try using a writing guide. You can also force yourself to write down something you've never considered or thought about before.

- Most writing guides have a time limit (e.g., “write quickly for five minutes”). You can increase the writing time limit if it doesn't seem like enough for you to collect story material. You can also "deviate" from the guide if your writing is going in a different direction. This guide should help you get started quickly, but not limit your writing.

- A writing guide can be anything from a sentence, like “I remember…” to a picture, like “Imagine you were trapped in your childhood bedroom.” You can also use a line from a favorite poem or book, or a snippet of lyrics to a song you like.

- You can find sample writing guides (in English) at https://www.writersdigest.com/prompts “Writer's Digest” and https://www.dailyteachingtools.com/journal-writing-prompts.html “Daily Teaching Tools”. You can also try doing a random online search at https://writingexercises.co.uk/firstlinegenerator.php “first line generator” (a help service for creating the first line for your story).

Step 3. Identify your protagonist

As you write the raw material for the story, you should take the time to reread it and see if the protagonist is already there. The protagonist is the character who unites the whole story. This doesn't mean that your protagonist has to be a hero or vice versa. The protagonist must be a character that readers like and follow, or who can get the reader's sympathy, including any mistakes or weaknesses.

The protagonist also does not always have to be the main point of view in the story, but must be a decision maker who moves the direction of the story. Your protagonist must drive the events of the story and his fate is at the heart of the story's meaning

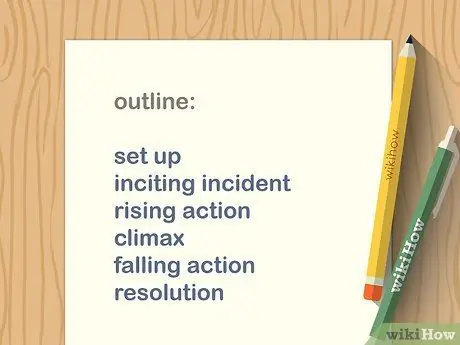

Step 4. Create an outline of the storyline

It will be easier for you to start a short story by writing an outline of the story line, because you will know what will happen along the way. Most writers avoid this because they don't want to feel constrained. But if you're having a hard time starting your story, it can help you identify the protagonist, the story's “mood”, and the events in the story.

- A storyline should first convey the story's target. This is something the protagonist wants to achieve and/or the “problem” he wants to solve. This is also called the big “wish” in the story, i.e. your protagonist wants something from himself, from another character, from an institution, etc.

- A storyline should also record the consequences that the protagonist must live if he doesn't reach his target. This is also called a “gambling” in the story, which makes the protagonist suffer if he fails to reach his target. Having a tense element of betting in the story will encourage readers to stay involved and care about the fate of the protagonist.

Method 2 of 4: Selecting the Opening Part Type

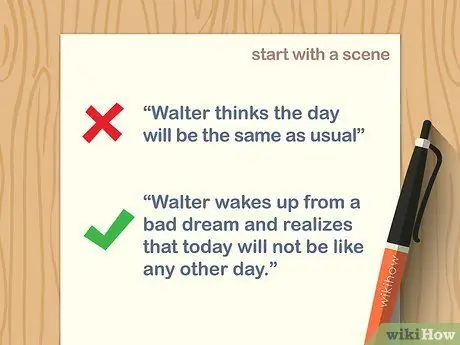

Step 1. Start with a scene

Many short story writers will try to start their story by presenting a certain scene, usually one that is important and catches the reader's attention. Start with a scene that will instantly captivate the reader and get them into the story.

- You should choose scenes that are important to the main character or narrator and indicate the roles these characters play in the story, when the characters do something that has consequences for the continuation of the story or determines the course of the story. For example, instead of starting with, "Revelation thinks today will be just like any other day," you could start with, "Revelation wakes up from his nightmare and realizes that today will be different from the days he used to go through.”

- While you may have decided to use past tense and grammar in your story, using present-day grammar will give your story a sense of urgency, and this will help readers keep wanting to read the rest of the story. For example, starting with "Today, I'm going to rob a bank" may be more effective than "Yesterday, I robbed a bank," because today's grammar makes the action seem like it's taking place. The readers can feel and experience what the characters in it are going through.

Step 2. Build the mood of the story

This type of opening is useful if the mood of your story is the most important and you want to build a certain “atmosphere.” Maybe your story doesn't have a heavy weight but has a certain atmosphere that you want to convey to the readers. You can use a character's perspective to describe the scene and focus on one detail that will amaze or grab the reader's attention.

- For example, in the short story “Oceanic” written by Greg Egan, the first sentences focus on building the atmosphere inside a ship sailing in the middle of the sea. Here is the Indonesian translation: “The waves gently tossed the ship. My breathing was slow, like my footsteps on the hull of a ship, until I could no longer tell the difference between the sluggish movement of the ship's cabin and the air moving in and out of my lungs." Egan uses certain sensory details to make readers feel the atmosphere that occurs in the ship's cabin and starts the story at a certain moment that he has determined.

- Keep in mind that you can also bring up the mood and scenes of the story in later chapters if you don't want to start right away by describing the scene. If the theme or plot is more important to your story than the atmosphere, you can start with these elements first. However, try to start your story in an atmosphere where the reader is directly involved in the story.

Step 3. Introduce your narrator or main character

Another option is to start with a strong narrative or description of your main character. This may be a good choice for a story that is driven by characters rather than by the plot. Often, the first narrator will begin with his words that set the story straight. You can show readers how the narrator sees the world and convey that narrator's view so readers know what they will get out of the story.

- Although the work of J. D. Salinger's title “The Catcher in the Rye” is a novel, not a short story, this story has an opening sentence that immediately brings out the voice of the person telling the story (translated into Indonesian): “If you want to hear it, the first things that come to mind are: You want to know where I was born, how messy my childhood was, how my parents were always busy before I was born, and all that other trashy stuff like David Copperfield, but I don't want to go into that, to be honest."

- The narrator's views are bitter and harsh but also take you into his frustration with this world and his distaste for common narrative habits. The narrator here has a different point of view which gives the reader an idea of the story as a whole.

Step 4. Open with a sentence of strong dialogue

Starting your story with strong lines of dialogue is effective, but it should be easy to follow and get the point across. As a general rule, dialogue in a story should always be about more than one thing and not just starting a conversation. A good dialogue will state the characters in the story and move the story from the events or plots that exist.

- Many short stories begin with one sentence of dialogue and then widen to tell the reader who is speaking or where the speaker is in the scenario. The dialogue is usually said by the main character or one of the main characters of the story.

- For example, in Amy Hempel's short story, “In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson Was Buried”, the story begins with a sharp line of dialogue (translated into Indonesian): “Tell me things I would easily forget,” he said. "Tell me useless things, or it's better you don't have to tell." The reader is immediately drawn into the story with funny, strange dialogue and the presence of a "woman" character.

Step 5. Present minor conflicts or mysteries

A good opening sentence should raise a question in the reader's mind, highlighting a minor conflict or mystery. This could be something as simple as the character considering what happened and his reaction to it or to a more complex mystery, such as a murder or a mysterious crime. Avoid presenting the mystery that is too excited or that immediately confuses the reader. Let the first sentence be a clue to a bigger mystery and ease the reader into the conflict of the story.

For example, the opening line in Jackson's short story, “Elizabeth” (translated into Indonesian), raises several questions for the reader: “Before the alarm went off, she was lying in the hot sun in the garden with green grass all around, and he spread his arms as wide as he could.” The readers are curious as to why the main character dreams about the scorching sun in the garden, why he wakes up, what the dream means in the next story for the character. This is a minor conflict, but it can be an effective way of making it easier for the reader to imagine the larger theme or core idea of the story

Method 3 of 4: Editing the Openings

Step 1. Read the opening section of the story again after you have finished writing it

While you may think you've put together the perfect opening to your story, you'll need to read it again once you've finished writing it, to ensure the success of your story. Sometimes, the story can turn out to be much more interesting and the opening may not be as great as you thought. Read the opening of the story again in the context of the whole story and consider whether the opening is still appropriate.

You can also change the opening at certain points to fit the atmosphere, mood, and gist of the whole story, or you may need to write a new opening to better fit the story. You can always save the old writing for the rest of your story in the future, especially if you think the opening is strong even if it doesn't fit into the rest of the story

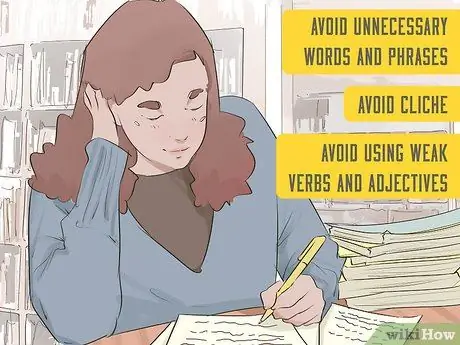

Step 2. Keep the language short

The opening section should not contain unnecessary words or sentences because they have little impact on the reader. Double-check your entire opening and make sure the language is strong and concise. Think about the clichés or “ordinary” sentences you use and replace them with something more interesting. Get rid of unnecessary descriptions or just give a description of the characters and the atmosphere of the story.

You can see the use of weak verbs or adjectives in the opening that feels weird and doesn't explain anything. Replace these words with stronger verbs and adjectives to give your opening a more “long-lasting” impact and set a high standard for the style and description used throughout the story

Step 3. Show the opening section of your story to an objective reader

Editing your own writing can be tricky, so try showing this opening section to a reader you trust. Consider showing your reader the first sentence or first paragraph of the story and ask if this opening makes him want to read the whole story. You should also ask if he gets an idea of the characters or the mood of the story when he reads the opening and if there are any improvements he suggests to make the opening part of this short story better.

Method 4 of 4: Understanding the Purpose of the Opening Section

Step 1. Always remember the role of the opening part of a short story

The opening part of the short story is important, because this part will determine the involvement and interest of the readers to continue reading the story. The first sentence or first paragraph often introduces the idea or situation that will be developed in the story. The opening section should provide clear clues about the atmosphere, style, and course of this story. The opening section can also reveal something to the reader about the characters and the plot of the story.

- Use the principle Kurt Vonnegut taught for short stories, which is a popular reference for writers, namely that you should always try to start “as close to the end of the story as possible” in the opening section. Get your readers right into the main action as soon as possible to keep them glued to read on.

- Often, editors will read a few lines from the opening of the story to see if the story is worth reading to the end. Many short stories are selected by publishers based on the strength of their opening parts. That's why it's important that you consider how you can make an impact on your readers and impress them with just the first one or two sentences.

Step 2. Read the sample opening sections

To help you get a better idea of how to start a short story, you should read some sample opening sections. Notice how the author grabs the attention of his readers and how his words are used. Some good examples are:

- "The greatest act of love I've ever witnessed was Split Lip bathing her disabled daughter." (“Isabelle”, by George Saunders)

- "When this story is heard throughout the world, I will be the most famous sissy in history." (“The Obscure Object”, by Jeffrey Eugenides)

- "Before the alarm stopped, he was lying in the hot sun in the garden with green grass all around, and he spread his arms as wide as he could." (“Elizabeth”, by Shirley Jackson)

Step 3. Analyze the samples

As you read through the opening section examples, ask yourself the following:

- How does this writer determine the atmosphere or atmosphere of the story? For example, the first sentence in Eugenides' short story “The Obscure Object” introduces the narrator as a sissy and lets readers know that the narrator's life story will be told. It sets a brooding mood, with the narrator revealing his life as a notorious effeminate.

- How does the writer introduce the key characters or moods? For example, Saunder's first sentence in his short story “Isabelle” introduces a character named “Split Lip” and his disabled daughter. This opening section also provides a key theme of the story: love between father and son. Jackson's first sentence in "Elizabeth" uses sensory descriptions and details, such as "sunburn" and "green", to paint a particular picture in the reader's mind.

- What are your expectations as a reader, based on that opening? A good first sentence will give the reader a clue as to what they are getting, and provide enough information to draw the reader into the whole story. The opening section of Saunders' story, for example, lets readers know that the story might be a little weird, with a character named “Split Lip” and a deformed girl. It's a powerful opening that lets readers know how the story will unfold with a unique narrative phrasing.