- Author Jason Gerald [email protected].

- Public 2023-12-16 10:50.

- Last modified 2025-01-23 12:04.

You have an idea for a play-maybe your idea is brilliant. You want to develop the plot to be either comedy or dramatic, but how? While you may want to get directly into the writing process, your drama will be more powerful if you spend a lot of time planning the story before you start writing the first draft. Once you have thought through the narrative and have outlined its structure, writing a play will become easier.

Step

Part 1 of 3: Thinking of the Narrative

Step 1. Decide what kind of story you want to tell

While every story is different, most plays fall into categories that will help viewers understand how to interpret the relationships and scenes they see. Think about the characters you'll be creating, then consider how you want to tell their stories. Wre they:

- Have to unravel a mystery?

- Through various kinds of difficulties to develop yourself?

- Growing up transitioning from innocent childishness to being experienced?

- Going on a journey, like the perilous journey that Odysseus took in The Odyssey?

- Putting things in order?

- Through various obstacles to achieve a goal?

Step 2. Think of the basic parts of the narrative arc

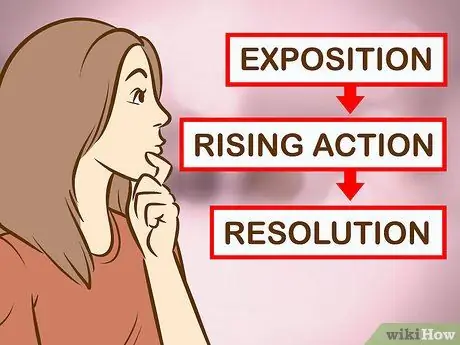

Narrative arc is the progression of the drama from beginning, middle, to end. The technical terms for these three passages are exposition, complication, and resolution-all plays must be written in that order. No matter how long your play will last or how many scenes you create, a good drama will build on these three parts. Note how you want to develop each section before writing the play.

Step 3. Decide what to include in the exposition section

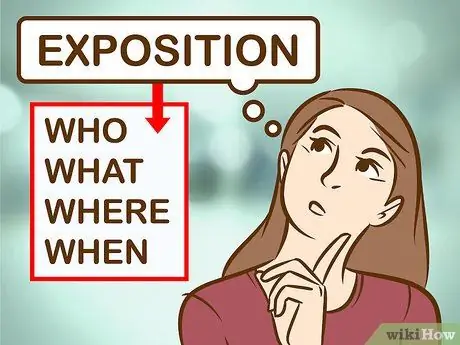

The exposition opens the drama by providing the basic information needed to follow the story: When and where does the story take place? Who is the main character? Who are the supporting roles, including the antagonist role (a role that presents a central conflict for the main character), if any? What are the main conflicts these characters face? What is the mood conveyed in your drama (comedy, romantic drama, or tragedy)?

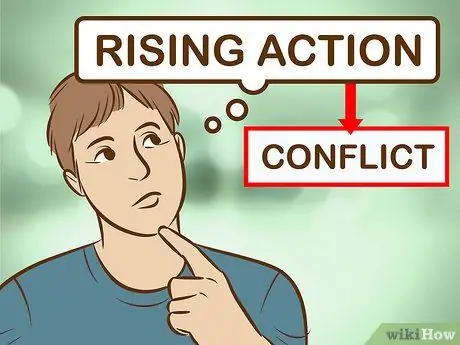

Step 4. Turn the exposition into a complication

In the complication section, the scenes will look difficult for the existing characters. The main conflict will become clearer as the scenes increase the tension of the audience. This conflict may occur with another character (antagonist), external conditions (war, poverty, separation from a loved one), or with oneself (having to overcome one's insecurities, for example). Complications will culminate into a climax: a scene when the tension is at its peak and when the conflict will heat up.

Step 5. Decide how the conflict will end

The resolution will relieve the tension of the climactic conflict at the end of the narrative arc. You get to have a happy ending-the main character gets what he wants; tragic ending-audiences learn something from the main character's failures; or settlement (denouement)-all questions answered.

Step 6. Understand the difference between plot and story

A play's narrative is made up of plot and story-two distinct elements that must be developed together to create a drama that will capture the audience's attention. E. M. Forster defines story as what happens in the drama-the opening of each event in chronological order. While the plot is the logic that connects every scene that occurs along the plot and strengthens it emotionally. Examples of the differences between the two are:

- Story: The protagonist's lover breaks up with him. Then, the protagonist loses his job.

- Plot: The protagonist's lover decides. Heartbroken, he fell into depression which affected his job so he was fired.

- You have to develop a compelling story and make the play run quickly so that it grabs the attention of the audience. At the same time, you have to show how these actions relate to the development of your plot. This is how to get the audience to care about the scene shown on stage.

Step 7. Develop your story

You can't deepen the emotional resonance of the plot until you have a good story. Think about the basic elements of a story before developing it with your writing that answers the questions below:

- Where does the story take place?

- Who is the protagonist (main character) of your story, and who are the other important supporting characters?

- What are the main conflicts these characters have to face?

- What are the “supporting events” that make up the drama's main action and lead to the main conflict?

- What happens to the characters as they face the conflict?

- How is the conflict resolved at the end of the story? How does this affect each character?

Step 8. Deepen your story by developing a plot

Keep in mind that the plot develops the relationships between all of the story elements mentioned in the previous step. When you think about plot, you should try to answer the following questions:

- What is the relationship between one character and another?

- How do the characters interact with the main conflict? Which characters will be most affected by the conflict, and how does the conflict affect them?

- How can you structure the story (scenes) to have each character confront the main conflict?

- Is it a logical and casual progression that connects one scene to another, thus establishing a continuous flow that leads to the climax scene and the story's resolution?

Part 2 of 3: Determining the Structure of the Drama

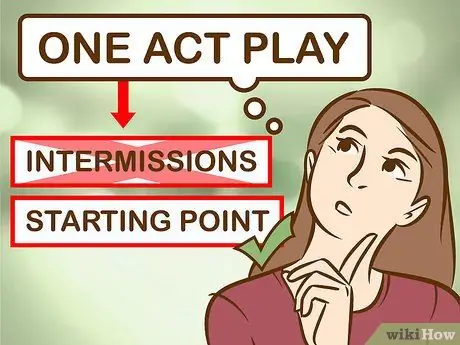

Step 1. Start with a one-act play if you are new to scriptwriting

Before you start writing a play, you need to understand how to structure it. The one-act drama goes on without a break, and it's the starting point for people who are just writing scripts. Examples of one-act plays are "The Bond" by Robert Frost and Amy Lowell, and "Gettysburg" by Percy MacKaye. Although one-act plays have the simplest structure, remember that all stories require a narrative arc with exposition, complication, and resolution.

Because there is no rest time, the one-act play requires a simpler setting and costume change. Simplify your technical needs

Step 2. Don't limit the length of your one-act play

The structure of a one-act drama has no effect on the duration of the show. The length of these plays can vary-some productions last only about 10 minutes and some more than an hour.

Flash plays are very short one-act plays and can last from a few seconds to 10 minutes. This type of play is suitable for school performances and community theatre, as well as competitions specially made for flash theatre. Look at Anna Stillaman's play "A Time of Green" as an example of flash drama

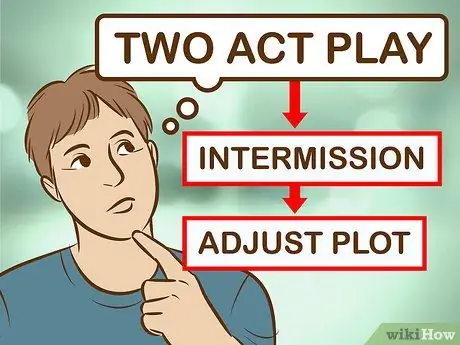

Step 3. Provide a more complex setting for the two-act play

Two-act plays are the most common structures found in contemporary theatre. While there are no rules that define how long a play's act is, generally speaking, a play's act lasts an hour and a half with a break for the audience between the two acts. The break time allows the audience to take advantage of it by going to the bathroom or relaxing, thinking about what happened, and discussing the conflicts that were presented in the first act. Plus, time off can also help the crew make major changes to the setting, costumes, and makeup. Break times usually last around 15 minutes, so arrange for the crew's tasks to be completed within that amount of time.

As an example of a two-act play, look at Peter Weiss' play "Hölderlin" or Harold Pinter's "The Homecoming."

Step 4. Adjust the plot to fit the structure of the two-act play

The structure of the two-act play doesn't just change the amount of time it takes the crew to make technical arrangements. Since the audience has a break in the middle of the play, you can't treat the story in the show as a flowing narrative. You should structure your story around intermissions to keep the audience tense and wondering at the end of the first act. When they return from their break, they can immediately get carried away in the complications of the story.

- Complications should arise in the middle of the first act, after background exposition.

- Follow the complications section with a few scenes that raise the tension of the audience-whether dramatic, tragic, or comedic. These scenes must continue to climb until they arrive at the main conflict that will end the first act.

- End the first act after the tension of the story is increasing. The audience will be impatient when given the break, and they will return excited to watch the second half.

- Begin the second chapter with a lower tension than when you ended the first. You have to remind the audience of the story and the conflict of the drama.

- Show some two-act drama scenes that increase the tension of the conflict towards the climax of the story, or when tension and conflict are at their peak, before the drama ends.

- Calm the audience towards the end with falling action and resolution. While not all dramas need happy endings, viewers should feel as if the tension you've built up along the way is over.

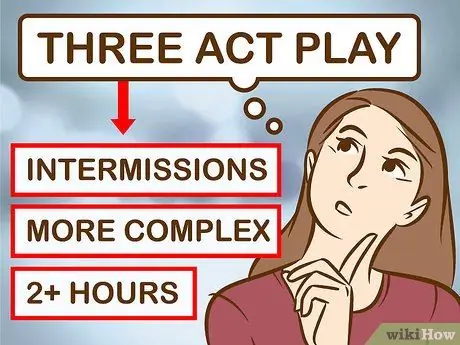

Step 5. Allocate longer and more complex plots with a three-act drama structure

If you're new to script writing, it's best to start with a one- or two-act play because a full-time play or three-act play will keep viewers in their seats for two hours! You need experience and the ability to put together a production that can hold the audience's attention for that long, so it's best to do a simple drama first. However, if the story you want to tell is quite complex, a three-act drama might be your best bet. Like a two-act play, this one lets you make major changes to the setting, costumes, etc. during the intermission between one act and another. Each act must be able to achieve its own storytelling goals:

- Act 1 is exposition: take the time to introduce the characters and each character's background. Make the audience pay attention to the main character (protagonist) and the situation to ensure an emotional reaction when there is a problem. Act 1 should also introduce issues that will develop throughout the show.

- Act 2 is a complication: tension builds up for the protagonist as the problem becomes more and more difficult to deal with. One good way to increase the tension in act 2 is to reveal a significant part of the character's background as they approach the climax of the act. This revelation must plant doubt in the protagonist's mind before he finds the strength to face the conflict on his way to the resolution part. Act 2 should end sadly and show all the plans of the protagonist falling apart.

- Act 3 is the resolution: the protagonist can go through the problems in Act 2 and find a way to get to the conclusion of the story. Keep in mind that not all dramas have happy endings; the hero in the story may die as the resolution of the story, but the audience should be able to learn something from this incident.

- Examples of three-act plays include Honore de Balzac's "Mercadet" and John Galsworthy's "Pigeon: A Fantasy in Three Acts."

Part 3 of 3: Writing a Drama Script

Step 1. Create an outline for the act and scenes

In the first two parts of this article, you've thought about basic ideas about narrative arcs, story and plot development, and drama structure. Now, before you start writing a play, you need to put those ideas into a good outline. For each act, write down what happened in each scene.

- When are important characters introduced?

- How many scenes did you make, and what happened in each of them specifically?

- Make sure each occurrence in the scene leads to the next scene so the plot can develop.

- When should you change the background? The costume? Consider technical things like this when devising how the play will be staged.

Step 2. Create an outline by writing a script

Once you have an outline, you can start writing your play. Write basic dialogue early in the story without worrying about whether it sounds natural or how the actor will move around the stage and stage your play. In the first draft, you have to make the “black on white” a play, as Guy de Maupassant puts it.

Step 3. Try to create natural dialogue

You should give them a strong script so they can say each line naturally, real, and emotionally strong. Record yourself reading those lines on the first draft, then listen to the recording. Take note of when you sound like a robot or overdo it. Remember, even in literary plays, characters have to sound like ordinary people. The character shouldn't sound like he's making a big speech while complaining about their work at dinner.

Step 4. Let the conversation intersect

When you talk to your friends, you rarely talk about one topic with full concentration. While in a drama, the conversation must lead the character to the next conflict. You'll need to make a few diversions to make it more realistic. For example, when discussing why the protagonist's lover broke up with him, you could include two or three lines of dialogue about how long they've been dating.

Step 5. Enter an interrupt in the dialog

Even if it's not meant to be rude, people often interrupt each other in a conversation-even if it's only with a word of approval, such as “Yes, I understand” or “Yes you are right”. People also usually interrupt themselves by changing the topic in their own sentences: "I just-I'm fine if I have to go there on Saturday, but- you know, I've been working overtime lately."

Don't be afraid to use fragment sentences. Although we are trained to never use fragmentary sentences when writing, we often use them when we are talking: “I hate dogs. Everything"

Step 6. Add a behavior or stage direction command

Behavioral commands allow actors to understand the image you have of performing on stage. Italicize the letters or use parentheses to separate the action command from the spoken dialogue. While actors will use their own creativity to bring your words to life, some specific commands you can give include:

- Command during conversation: [long awkward silence]

- Physical commands: [Santi stands up and paces nervously]; [Marni biting her nails]

- Emotional state: [fearfully], [enthusiastically], [picks up a dirty shirt and looks disgusted at the sight]

Step 7. Rewrite as many drafts as needed

You won't be successful right away when you create a play on your first draft. Even experienced writers have to do several drafts before being satisfied with the final result. Do not rush! Add more details that will bring your show to life each time you reread the script.

- In fact, when adding details, keep in mind that the delete button can be your best friend. As Donald Murray said, you have to “cut out what is bad, and show what is good”. Remove all dialogue and scenes that do not cause emotional resonance in the drama.

- The advice of a novelist named Leonard Elmore can also be applied to drama: "Try to leave the part that the audience will skip".

Tips

- Most dramas are set in a certain time and place, so you have to be consistent. Characters in the 1930s could make calls or send telegrams, but couldn't watch TV.

- Check the resources at the end of this article for a good drama format and follow the guidelines.

- Be sure to keep writing the script if during the show you forget a line, make it up! Sometimes, the result will be better than the original dialogue!

- Read the script aloud to several viewers. Drama is based on words and the power they produce, or the absence of them will tell.

- Don't hide your play script so you can be called a writer!

Warning

- The theatrical world is full of ideas, but your treatment of a story is original. Stealing other people's stories not only makes you immoral, you can also be thrown into prison.

- Rejection will certainly trump acceptance, but don't be discouraged. If you are constantly disappointed that one of your manuscripts was rejected, create another.

- Protect your work. Make sure the title of the play includes the name and year it was made, followed by the copyright symbol: ©.